#SingleFamilyZoning Part 4 - The Conclusion

Folks, I love a good series. And, generally, I’ve been pretty good at finishing them. There was Allies Parts 1, 2, and 3. A four-part series on justice reform (#YouthJail, #YouthJustice, #CharleenaLyles (or #DisarmPolice), and #Freedom (or #JusticeReform)). A 10-part series on #HALA.

This time around, we took a trip through Single Family Zoning, starting with a piece outlining why I center racial justice in my approach to land use, diving deeper into redlining’s past and effective present, and spending time specifically unpacking displacement risks and causes. Ultimately, the data is clear: our city’s reliance, much like other cities’ reliance, on detached single-family zoning protection as a key component of zoning and land use is having a disparate impact on communities of color. Further, it is harming the ability for more families to obtain stable housing, particularly through homeownership. The environmental impacts of preserving (overwhelmingly white) detached single-family zoned areas of the city are felt most acutely by communities of color.

Current approaches to address affordability and displacement continue to be centered on single-family protectionism in white neighborhoods. And even where there is a push to change zoning for more housing diversity, the push-back is to cluster new households along arterial roadways where air pollution is worst. This approach, while admirable in its goals of adding more housing options, is likely to exacerbate negative health outcomes for residents, in particular low- and moderate-income households. Continued efforts by the city to roll-back green transportation infrastructure are going to exacerbate these negative outcomes and, just in time to match historical trends, will result in pollution worsening in communities of color at a faster clip than white neighborhoods.

There are bright spots on the horizon. For one, the Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) legislation that is currently held up by predatory delay tactics from white anti-housing activists has completed its Hearing Examiner hearing process, and written closing arguments are due in the middle of April, with a final decision expected by early to mid-May. During the budget process for 2019, Councilmember Mike O’Brien was able to get funding included to begin the process of allowing Office of Housing dollars to be spent as grants to property owners looking to add an Attached Accessory Dwelling Unit (AADU) and/or Detached Accessory Dwelling Unit (DADU) in exchange for income and rent limitations. These are good ideas that, if targeted to homeowners who are at greatest risk of losing housing due to gentrification and displacement, can be a solid anti-displacement tool.

Of course, what has been missing from all of my writing: what is the actual cost associated with Single-Family zoning changes, and how could that impact homeownership opportunities throughout Seattle, and be done in a way that advances equity and environmental stewardship first, with protectionism of white neighborhoods as an afterthought?

As an initial matter, there is a fundamental values question. Is homeownership a goal we, as a society, should be supporting? As a rule, I believe we should. Taking a step back, I’m generally uneasy with the concept of property ownership, and would favor a model wherein government owned all land with land-leases for improvements. At the same time, I’m a realist. Even in Seattle, this is a minority position. So, instead, I look to what creates the most stability for households. As reported recently, since 1960, rents have gone up a staggering 61% (adjusted for inflation) while renter incomes have risen only 5%.

Conversely, while the price of homes for purchase has increased significantly over the years, once someone actually purchases, the annual increases in monthly housing costs (mortgage + taxes + utilities) remains relatively stable. Ownership provides the most likely route for housing cost stability, which is a crucial way to avoid entering homelessness. (Rent stabilization could provide an additional avenue for households unable to afford to purchase, but the concept, as appealing as it is for liberals in Seattle, is a continued non-starter in the State Legislature, where action would have to occur to authorize any sort of stabilization measures to be implemented locally. At this point, it’s a bumper sticker, not a real-world plan for the near-term).

For a starting point: the median market value for a home in Seattle, according to Zillow, is just under $730,000. For a detached single-family home, it’s $761,000, and for a condo/co-op about $487,000. The median per-square-foot listing price is $521/square foot. Of course, the actual prices vary wildly depending on which part of the city you’re in.

Looking to new construction, I checked in with someone who does smaller-scale development (as an architect), and asked about the cost to design and build an ADU (both AADU and DADU), as well as the cost per-square-foot to build stick-built attached family housing.

Starting with ADU’s, he estimates that new construction for a DADU, from design to occupancy, runs between $250,000 and $350,000. An AADU can see costs reduced by about 20%, or $200,000 to $280,000. For comparison, the per-unit cost for a 2-bedroom unit rent-restricted unit (with city money) is about $384,000.

Currently, ADU’s are limited to 800 square feet, suggesting that the cost-to-build is about $375 per square foot. Assuming a 900 square foot 2 bedroom (which is pretty large, frankly), the per-square foot cost for rent-restricted units (typically in five to seven story building) runs just under $430 per square foot. So, right off of the bat, ADU’s can provide a lower-cost option for rent-restricted homes, and if the EIS is upheld, could be as large as 1,000 square feet. But also, by not restricted them to urban villages, these could instead be closer to parks and schools, improving family-health outcomes for low-income households.

As for attached-family housing, this is where it gets interesting.

Our current regulations allow the smaller house to be replaced with something much larger, but still only providing a home for one family.

To begin with, as the city moves forward with consideration of zoning changes, it should be cognizant of the environmental impacts of tree canopy loss. As advocates rightly note, tree canopy in the city helps “filter” the air, provides shade on hot days, and improves the quality of our neighborhoods. However, protectionism of single-family zoning, with minimal restriction on lot coverage, has not only led to more McMansions being built, but has also led to single-family zones leading the way for tree canopy loss in the city.

Current Regulations In Practice

The ADU legislation’s Environmental Impact Study (EIS) looked at a way to decrease the prevalence of tree canopy loss in single-family zones: implementation of a Floor-Area-Ratio of 0.5, or 2,500 square feet. What that means in practice: if adopted, new single-family homes could not have more square footage than 50% of the total land, with exemptions for a partially below-grade ADU, or a detached ADU. If we were to take this concept, and bump it to 0.6, allowing one attached-residential home for every 1,500 square feet of lot, our city could be in a position to authorize attached family housing while discouraging McMansions, and actually protecting tree canopy. At the same time, we would create new opportunity for homeownership opportunities, with family-size unites, near schools and parks.

Take a 6,000 square foot lot, for instance. Using $200-250 per square-foot for “medium quality” construction, the cost, excluding land and profit, for four attached units would be $675,000. For a market-rate development, a mark-up of 25% could be expected, adding $168,750 to the cost of the project. The only thing missing: the land cost. Let’s use that $761,000 figure from above, and assume a teardown. Combined, the cost to build the four attached units, inclusive of profit and land cost, would come in at $1.6 million. Or, put another way, the average cost to sell: $401,187.50. That is a helluva lot lower than the $761,000 for the detached single-family house replaced (a house that likely has other issues, such as poor insulation). It’s even lower than the average condo/co-op cost. And in this scenario, it could be four 750 square foot units; three 850 square-foot units and one 450 square foot unit, or any sort of combination. In addition, the FAR limit would necessarily disallow a bulky structure “out of character” with an existing neighborhood.

What was once legal also matches “neighborhood character”

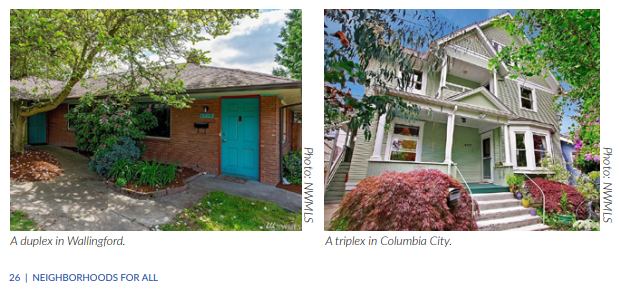

Of course, allowing attached family dwellings would not only allow for new construction, but also division of existing detached single-family homes to accommodate more families. Splitting old craftsman houses into duplexes and triplexes could be readily done, and having that be all rentals, or a homeowner downsizing into one unit, or a cooperative living situation, by adding more homes, the cost for families is decreased (all while increasing access to community assets).

The impact goes beyond the market: by allowing for more housing diversity, community land trusts (such as Homestead and Homesight) could find themselves positioned to create more homes and more homeownership opportunities for low-income households, stretching public investment in this strategy even further. It’s a win/win.

What once was, and could be again

Implementation of any change to detached single-family zoning is tricky, of course. As we have seen with historic zoning changes, communities of color are targeted for displacement and gentrification. I would defer to a racial equity analysis that leads with those most impacted by the housing crisis (renter households of color), and would offer only this: any plan must be implemented north of Ship Canal first, and provide an opportunity for a series of attached housing to be built and bought by families looking to buy that cannot afford Ravenna, but can afford Hillman City. Creation of affordability at Hillman City levels in Ravenna is going to be key to mitigating displacement and gentrification from people looking to buy.

Ultimately, moving to a Residential Zoning designation, as proposed by the Seattle Planning Commission, doesn’t have to mean ending zoning. And it shouldn’t. I’m not opposed to zoning, and believe that it can be done in ways that, through smart planning, ensure public investments are not being overly stretched. However, our current zoning practices are overstretching those public investments through a deliberate effort to focus all housing in a few parts of the city.

By opening up the entire city to more housing diversity, and doing so with appropriate FAR limits and parking considerations (I would propose a 1-spot per unit, entry to the spot from the alley, for all Residential Zoning), we can achieve a gentle-infill of housing types that create opportunity. By implementing a plan with intention to mitigate - or even reverse - displacement of communities of color, we can better weave social and racial justice into our land use policies.

It will take political courage and leadership to make the change, and to work with willing communities to build support for such a concept. But I wholly believe our city is ready for this change. Broadly, single-family preservationists have fared poorly at the ballot box, with one glaring exception. This election cycle will be another opportunity to see how far voters want our city to go.