#SingleFamilyZoning (Part 1 in a series)

Recently I participated in an anti-racist workshop. It was not the first time I’ve been in a training or workshop around racial equity, and likely won’t be the last. I am a firm believer that white folks need continuous, affirmative training in order to be most effectively anti-racist, and too often it is easy for us to slip into comfort around what work we are doing to embed equity in our day-to-day lives.

An important component of the workshop was the notion of “calling in” rather than “calling out.” While “calling out” was affirmed as necessary in instances where immediate circumstances create a need to intercede in a particularly egregious behavior, the emphasis of this workshop was working to find ways to bring people who are reasonably likely to be amenable into the broader cause of being actively anti-racist. Lord knows I have not always been the best at this concept, and have too often relished in the trenches of the keyboard wars. It’s a character flaw that I acknowledge and continue to try to improve upon.

Don’t get me wrong – I will highlight ridiculousness and utilize snark regularly, but I continuously aim to not “punch down,” and focus on arguments against ideas that are not well-rooted in fact rather than tearing people down. I have famously failed in this regard at times, but broadly it remains something on which I personally remained focused.

I know what you’re thinking – Michael, this post is titled #SingleFamilyZoning, what does this soliloquy have to do with zoning?

That ultimately depends on what you believe “anti-racist” means.

For those who have been paying attention, Seattle recently adopted the Mandatory Housing Affordability legislation. MHA is, to be blunt, an extraordinarily conservative effort to increase housing stock, with a minimal contribution from developers to match the minimal density change associated. During the full council meeting where the final vote occurred, Councilmember Lorena González delivered the history of Seattle’s Single Family Zoning, the redlining that occurred thanks to (at the time legal) race-restrictive covenants, and noting that it took nine years for the City of Seattle to adopt the Open Housing ordinance.

Watch CM González’s entire speech. It’s amazing.

Even today, and despite the Community Reinvestment Act, banks continually deny loans to similarly qualified households of color, creating a modern-day redlining.

The natural result of public policy endorsing racism in housing: inequitable wealth distribution, inequitable homeownership, and, combined with historic disinvestment in community assets, affirmative barriers to fair housing, quality education, transit, childcare, food, and family-wage jobs. In Washington, the passage of I-200 in 1998 further denigrated efforts to infuse equity into public works projects, harming access to wealth and building of equity for women and minority-owned business enterprises (WMBEs).

Furthering this inequity, we also see households of color more likely to be renters, and thus more likely to be adversely impacted by increasing rents, leading to economic displacement. As white folks get less racist, and move into neighborhoods where black and brown families were forced as a result of redlining, and where these families built community, we not only displace families from housing but, in true colonizing form, bring in overpriced cupcakes and gourmet hot dogs, displacing community institutions and small businesses. We kill culture.

Michael – where is this going?

A major belief I have taken with me from the trainings and workshops I have done around anti-racism and dismantling privilege is that, where institutional white supremacy continues to benefit white people inequitably, we must look at those institutions and ask what could be done to reverse the effects of their history. Where existing systems will necessarily have inequitable outcomes for communities of color because of historic inequality, those must be observed and we must take action if we are truly going to engage in racial justice. Simply acknowledging something was rooted in racism, but declaring its continuance not necessarily racist because “I’m not racist” is folly, in my ever so humble opinion.

And that’s what this has to do with single family zoning.

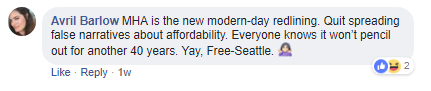

Throughout the MHA timeline, we began to see unfortunate trends. White folks purporting to speak for communities of color in order to prevent more neighbors in the white folks’ neighborhoods. White folks saying that MHA is “the new redlining,” a particularly offensive remark. White folks lecturing younger folks about their housing choices. Hell, I was in a meeting with members of SCALE, and when the one person of color in their crew was speaking, a white dude tried to interrupt her and explain what she really meant.

The ongoing harms of these zoning practices is well-documented, and we see communities of color suffering the impacts of prior policies placing industrial lands and freeways near black communities. But even MHA’s “compromises” continues this trend, continuing to shoehorn development along arterial roadways, and providing less opportunity for gentle infill in order to appease predominately white property owners. As noted above, people of color are much likelier to be renters, and with the parts of cities with the best air quality restricted from attached-family housing, we are making an affirmative choice to continue perpetuation of negative impacts of climate change disproportionately toward low-income households and communities of color.

The stark reality is this: we are reckoning in Seattle with our affirmatively racist history, and that is uncomfortable for white people. Acknowledging that we continue to benefit greatly from institutional racism is hard. Staring down potential changes to our built environment that mean change to what we see can (and does) create unease. Expecting others to adhere to what we believe is the “right” way to live is a colonial tactic, and difficult to overcome.

But it will take white people affirmatively working to undo institutional racism to actually make change stick.

Part 1 in a series