#SingleFamilyZoning Part 2 - #Redlining

All fourteen of you are likely aware that I have decided to do a series on detached Single Family Zoning. This kicked off earlier this week with a bit of an intro piece that was designed most to set the stage and hopefully help folks understand the lens with which I am using when discussing zoning issues.

In that piece, I noted recent comments coming from white property owners that the recently passed Mandatory Housing Affordability is the new “redlining,” and noted that this statement is offensive. A friend reached out following noting that while I highlighted this, I didn’t necessarily do much (if anything) to rebut the statement. In their view, arguments such as these appear to be framed as concern for low-income households and communities of color. And I don’t disagree. That said, as Councilmember Sally Bagshaw noted, just because you say it doesn’t make it true.

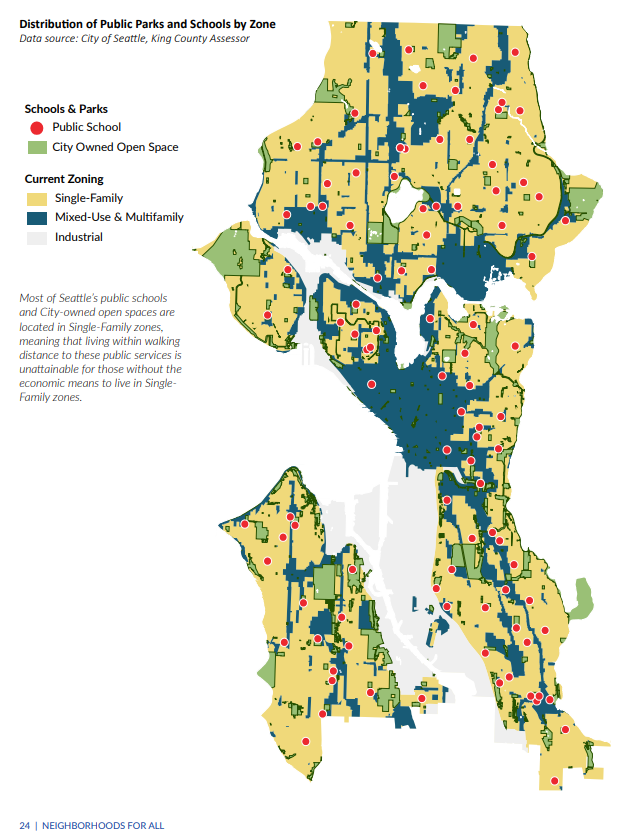

First, let’s take a brief trip down memory lane. The original redlining practice essentially meant that housing would come complete with covenants that disallowed persons of color to reside in the the homes. When we look at redlined maps of cities across the country, this often meant that areas with access to parks, schools, transit, and further from industry, were reserved for whites, leaving areas that did not have that same access, or same distance from industry, as the only place that households of color could live.

It took awhile, but eventually that practice was outlawed. Yet that did not stop financial institutions from creating maps of their own detailing areas where they simply would not lend, identifying them as “hazardous.” These areas were, more often than not, the communities that were left for households of color. As former Department of Planning and Development Director Diane Sugimura can tell you, it wasn’t just the banks. During a forum on anti-displacement strategies within which I was a participant, she told the story of being a young girl, and her family wanting to buy houses in areas that could no longer legally ban them, but de facto did, with real estate agencies refusing to show homes in white neighborhoods. Even now, financial institutions continue to deny loans to qualified households of color at alarming rates compared with white households, all while federal regulators continuously dole out “compliant” determinations for 99% of lending institutions.

Add in decades of disinvestment in communities of color, institutional racism in employment and education, and the creation of a funding mechanism for community assets that over-relies on voter-approved levies, and we have a significant problem right here in liberal Seattle.

Over the years, we have seen this play out in land-use policy. When you look at maps of urban villages, and prior expansions, ever-so-often we see white neighborhoods able to (successfully) fight housing diversity, pushing new development into communities created by households of color in the face of adversity in public policy. Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda often notes that, when we look at the historic manner in which we have made land use decisions, it’s no wonder those most at risk of displacement are concerned about new development and development capacity. These communities have seen the impacts of gentrification and felt physical and cultural displacement the most, and along the way the response of policy-makers to bake in true equity has been lacking.

I was having a conversation prior to the MHA vote about this inequitable application of land-use changes over the years. From my perspective, this is why it is vital that we start a transformation in how we apply new changes, and that is likely to mean more significant changes in neighborhoods that have successfully fought change over the past decades. Those fights have been a contributing factor to gentrification and displacement in the Central District, the CID, and Southeast Seattle, and if we are going to address growth equitably, I would posit that means those white neighborhoods should take on more, as a proportion of total growth, considering they have taken a disproportionately smaller amount over the past 25 years.

Above all, however, I do not believe it is appropriate to compare MHA to redlining, in particular considering that many of the more robust changes are occurring in white neighborhoods.

To the extent MHA is creating a “new redlining,” that is directly as a result of efforts to preserve detached single-family zoning. Councilmember Juarez highlighted the adverse impacts of concentration of density on arterials when the Council was discussing amendments to the MHA legislation in Crown Hill. There, a proposed “density swap” was done in a way where multifamily development is essentially reserved to be along the least healthy part of the neighborhood - traffic-filled 15th Ave NW. The way we have directed growth since the original adoption of the Urban Village Strategy emphasizes placing multi-family housing along exhaust-filled arterials, I-5, and Highway 99. And multifamily housing is where we are most likely to find low-income households and renters. And to reiterate, families of color are much more likely to be renters.

This has been my problem with MHA all along, is that it reinforces a growth policy that shoehorns growth into so few areas, and does very little to address detached single-family zoning, perpetuating a racist history in land use in Seattle.

There are other very important concerns that routinely are brought up regarding displacement of households when new development comes to communities throughout the city. This is where MHA, and upcoming policy changes addressing displacement, are extremely important. Way back when the legislation was first sent down by then-Mayor Tim Burgess, I did a freelance piece for the South Seattle Emerald, in which I noted that the statutory side included the new “M” designations that were specifically designed to be part of a displacement mitigation strategy. Councilmember Herbold is working on additional measures that will likely be part of the Funding Policies, including efforts to grant first-right-of-return for qualified households physically displaced, and to build on Councilmember Mosqueda’s efforts in the surplus land disposition policies to ensure more community-ownership in areas at highest risk of displacement. These are good measures.

The alternative to MHA - doing nothing - would have exacerbated displacement even more. As I wrote in Crosscut back in 2016, the concept of relying on benevolent landlords is poor public policy. Having a program in place that can pass legal muster and create more community-ownership, along with adoption and implementation of policies expressly designed to affirmatively further fair housing (especially at a time when the federal government is ending federal programs that do the same) is crucial. Otherwise we would have a system where developers can do whatever they want, and we would just have to hope that more developers engage in social justice as part of their mission.

As this all relates to single family zoning and the concept of redlining, however, I must disagree with the notion that MHA is “the new redlining.” If anything, the data informs us that perpetuation and clinging to detached single family zoning is “the new redlining,” and it looks a lot like the old redlining.