#Homelessness & #FundingSolutions

One of the recurring themes in every racial equity and anti-racist workshop and training in which I have participated is that we (white people) need to work on “calling people in.” The concept as I understand: identify where we may be able to brought in to support anti-racism work, and do the same. I wrote briefly about this concept when kicking off the #SingleFamilyZoning series, and highly recommend white folks consider the Anti-Racism training offered by the Coalition of Anti-Racist Whites. It’s very good.

“We are failing our neighbors experiencing homelessness, and we are failing our community as a whole, and we can’t pat ourselves on the back for investments when the need continues to outpace our effort. We also should not engage in efforts proven to exacerbate trauma by simply move people around when those resources should go instead into housing.”

This concept is something that I believe can (and should) be replicated in other work to change institutional culture around our homelessness response. While people can (and do) bicker over who’s more right from the comfort of their homes, people are dying outdoors. Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda said it best back in January of this year. In one of her #TeresaTuesday emails, she highlighted the good news that Seattle was investing $75 million in affordable homes in 2019. But also reminded us of the stark reality: this is nowhere near enough.

I could quibble more with the investments themselves (about 188 potential new units for households exiting homelessness out of 1,200 total units), but how Office of Housing investments work, specifically the funding streams, inform me that they were generally good within the constraints of the law. Also, the need is great across the spectrum in the 0-60% Area Median Income (AMI) range, and many households living in 30-60% AMI housing are well below 30% AMI - 30-60% prevents homelessness. At the end of the day, the team at Seattle’s Office of Housing - from Director Steve Walker to all of the staff - have done amazing work to stretch local investment very far, maximizing the total amount of permanently affordable homes that will come online in the coming years, and that will save lives.

We know what works to end homelessness: homes. It’s as simple as that. Our region has nowhere near as many homes affordable to low- and very-low-income families as we need, and we are severely lacking in supportive housing, as well - both units and services. I had the distinct pleasure of co-writing a piece about permanent supportive housing specifically this past Monday with Professor Sara Rankin from Seattle University School of Law (a local expert on homelessness and effective responses). tl;dr version: we know what works for individuals who are chronically homeless and have high-supportive needs. We just don’t have enough of it.

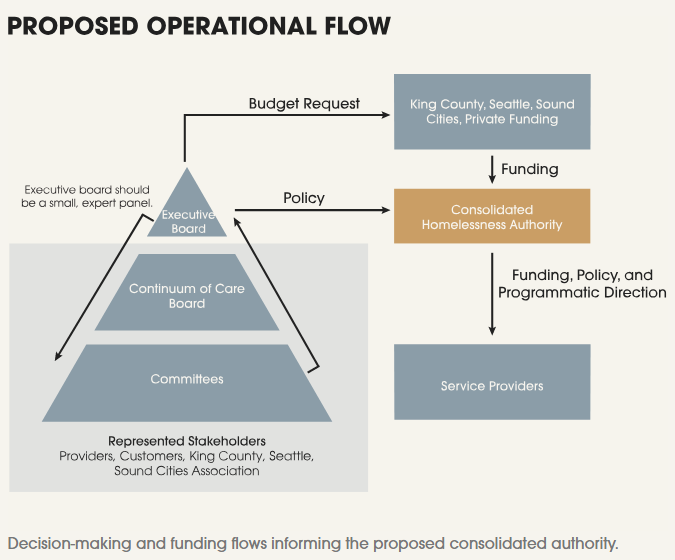

So, how do we actually begin scaling up our investment? For starters, our region needs a cohesive strategy to meaningfully reduce homelessness, both short-term strategies and a long-term investment plan. My experience over the years working on homelessness issues is that there really hasn’t been good coordination, or a clear vision for what the hell it is we are doing. There are signs that meaningful action is finally being taken (over three years after a declared State of Emergency). Future Laboratories, led by Marc Dones, has participated as part of a team of consultants, has given our region actionable steps to begin institutional, transformative change in how we approach solutions. Generally, I believe that all of these systematic approaches should be adopted, with adequate funding to make them successful.

At the same time, the city and county must begin work, in collaboration with providers, people with lived experience, and the community at-large, on a workable strategic plan. The fact is we need more money to meet the regional homelessness crisis need (and any candidate who says otherwise is likely unqualified for public office). At the same time, our governments must do a far better job of making clear where that revenue is going to go, and why.

This concept of a plan reminds me of the conversations at Seattle City Hall regarding the Employee Hours Tax in 2018. At the time, there were not only criticisms of the revenue source itself, but also assertions that there was no “plan” for spending revenue. That assertion is wrong.

In fact, there were two plans floating around, each with a different goal in mind. One was focused overwhelmingly on emergency and enhanced shelter funding, with a goal of creating more places for people to be that were indoors in the short-term. I took issue with this approach primarily because, in my view, this was setting up a situation wherein we would fund shelter, cutting it off after 5 years, and without a plan, or even a plan to create a plan, to scale-up investments in supportive housing and other measures to ensure that beds in shelters were rotating quickly. Data shows, for instance, that enhanced shelter is the most successful connecting people with permanent housing. All the same, if there isn’t permanent housing available, it’s success is severely limited.

The plan that was adopted by Council, however, was focused on transitioning dollars into permanent housing on a reasonable timeline with the 5-years of the tax. Also known as Version 6, as new permanent housing and supportive housing was anticipated to com online, funding for basic shelter and additional encampments funded through the EHT was essentially zeroed out as the 302 units of supportive housing were anticipated to come online. In addition, Navigation Team funding was ramped up in year 3 - the year that the first supportive housing units were anticipated to come online (and the year after a 50-bed bump in enhanced shelter was anticipated).

That said, the EHT was never going to be enough. 302 additional units would have made the difference for those households, but the need is more than 10 times that amount.

In the midst of the EHT debate, it was discovered that the Seattle Chamber of Commerce has partnered with McKinsey & Company, resulting in a report that analyzed existing services, and what the regional need would be to effectively end homelessness in our region. While working for Councilmember Mosqueda, I did a quick overview of the information presented by McKinsey, compiled in a memo that essentially argued for more regional investment in human infrastructure, while also outlining different ways to look at the “proportional share” between the City and the County to meet the McKinsey figures (an updated memo, referred to as “the Blue Memo,” further dove into limitations of the McKinsey/Chamber report, notably that it appeared focused on services only, not capital needs). During a committee meeting, Councilmember Herbold cited my memo (turning it from “Draft” to “Final”) as evidence that the $500 per employee was an appropriate number to reach Seattle’s share. Councilmember Bagshaw also cited the same memo to highlight the need for the rest of the county and region to pony-up more money.

Ultimately, following the repeal of the EHT, and without any meaningful approaches being taken to identify a pathway toward a solution, I was tasked with poring over all of the information I could find to (a) fully opine on the total capital need across the County for both supportive housing and rent-restricted housing for households up to 30% Area Median Income and (b) identify potential resources to pay for that construction. This work, in collaboration with Central Staff, other Council Office staff, elected officials from across the state, and experts from across the state, led to The Green Memo, a document so long I had to create a summary memo for the memo.

This covered various issues, including dispelling the myth that the City could make any meaningful change from existing resources, drawing parallels with Los Angeles, putting a dollar figure on the need, and identifying potential funding streams. Cut from the final version: the per-day cost of incarceration and treatment. Most of the figures I used were based off of the McKinsey/Chamber report, because that is what it appeared we could all coalesce around as an agreed set of facts.

So what is the bottom line?

The Need

Looking at the McKinsey Report, with some help from the Regional Affordability Task Force study, our County needs an additional 3,200 (at least; the Third Door Coalition suggests the number is upwards of 4,500) of permanent supportive housing to meet the need today.

Our region needs at least 10,800 units of income-restricted, public housing, for households making 30% Area Median Income or less.

Our region needs 65,200 units of housing that is attainable and affordable to households making 30% of Area Median Income or less.

Put another way: our region needs public investment in capital construction of supportive housing to the tune of nearly $1 billion.

Our region needs public investment in capital construction for public housing for extremely-low-income households of over $3.3 billion.

Our region needs either investment in construction for housing attainable to households making 30% or below Area Median Income of over $20 billion, through a combination of private investment, direct rental subsidy, and/or cross-subsidy in mixed-income communities.

On top of this, our region needs ongoing funding for services to the tune of $200+ million per year to meet the need.

That’s a lot of money. And to many, it likely seems insurmountable. The good news: it’s not.

As an initial matter, our region needs more investment from the federal government. Ongoing cuts to housing programs have made it impossible to ensure that all households have access to safe and sustainable housing. Continued cuts from the federal and state government in social services have limited the ability for local governments to meaningfully address homelessness for individuals with untreated mental health conditions or substance abuse disorders.

Looking specifically at people experiencing homelessness that are classified as “hardest to house,” as was discussed in the Urbanist piece earlier this week, the costs of inaction are significant. It’s an old study, but back in 2010, as part of the 10-year Plan to End Homelessness, an analysis was done of the costs associated with a more intensive supportive housing model used by Plymouth Housing Group (the Begin At Home program). Relevant here, the data showed a reduction in service utilization (funded primarily by tax dollars) of $62,510 per person, with a program cost of $18,600 per participant. If we were to operate under an assumption that the 3,200 households identified as most likely needing permanent supportive housing would fall into this category, over ten years, if we had the service available at scale, total savings to taxpayers would be approximately $1.4 billion. Looking at it another way, the cost of inaction - of maintaining the status quo - is over $2 billion over 10 years, versus the cost of providing the service (minus capital) coming in around $600 million. The other difference: doing nothing not only costs more in service utilization, but also means we still have tents on sidewalks and refuse in medians. Doing something means we not only ease human suffering, but also see actual cleanups of communities with neighbors forced to live outdoors because of lack of options.

But how do we pay for it? Here’s the rub - we can’t “tax the rich” out of this self-made crisis. Given constitutional and statutory limitations, we are stuck with regressive tax options. That said, I do not believe we have time to wait for better revenue options. And we may have, either now or in the near future, funding tools available to us now (or soon), including:

0.1% Sales Tax across King County, which may unlock up to $500 million in bonding capacity;

A bond against property taxes over 20 years, county-wide, to raise at least $750 million;

A State Sales Tax Credit that could mean a potential $200 million per year, county-wide, that could be spent on housing and services;

REET III or a graduated REET, providing additional revenue for capital needs.

In an ideal world, we would also be talking about a local capital gains tax on high-value property transfers, but that would require legislative approval. And, of course, a graduated income tax, which would also require legislative approval (and overturning of Culliton v. Chase).

The two biggest-ticket items to fund capital needs require voter approval. This is why a strategic plan is so vital, and why it is crucial for our elected leaders to effectively collaborate and communicate why scaling up investment in the billions is the right move now, while continuing to fight for more capital funding for rent-restricted homes, and programmatic funding for diversion and permanent rental-assistance programs.

There are a lot of alternative housing models to meet the needs of individual households, and as some people point out, not everyone experiencing homelessness needs the full wrap-around services of our permanent supportive housing models. Los Angeles Homelessness Services Administration has been investing in different strategies and innovations with success (including more progressive-engagement strategies) since the passage of the “H” and “HHH” measures. With a regional homelessness services administration agency, we can unlock more options to meet the needs of households that fall between needing PSH and simply needing permanent rental assistance. And openness to this will hopefully be included in any strategic plan presented as part of a proposed funding package.

At the end of the day, we know what works. And thanks to countless hours of research and studies, we know how much we need. Now we simply need our local governments to prepare a revenue source, and strategic plan, and give voters what they want - a reason to vote yes for a massively scaled-up approach to our homelessness response. And this will be the true test of how committed Speak Out Seattle really is to “evidence-based” approaches.