#Taxes

In 2018, the Seattle City Council was considering legislation to amend the spending options for the Transportation Benefit District. After years of work, led by students at Rainier Beach High School, this included funding ORCA cards year-round for Seattle Public Schools students. In addition, there was a change to allow funds to be used for capital projects to improve transit service. The other major change: using TBD funds to pay for a private company to provide additional transit service beyond what King County Metro was able to offer.

What led to this: King County Metro has been unable to “sell” extra service to the City of Seattle as contemplated by the TBD Proposition 1 measure passed in 2014. For those who need a refresher: facing budget shortfalls, King County was unable to ramp up service for transit to meet demand. After a county-wide measure to increase revenue failed, Seattle used the Transportation Benefit District authority granted by the State to put a ballot measure to voters for a flat-fee of $60 per vehicle registration, and 0.1% increase in the City sales tax. This was on top of the $20 flat-fee per vehicle registration that was already adopted by the City (the maximum allowed without a ballot measure).

Since that time, King County Metro has not had the capacity to meet the needs of Seattle residents. Depending on whom you ask, this is a result of driver recruitment problems, and/or lack of space to park buses when not in use. As a result, the TBD has under-spent revenue recovered for years.

Back to 2018 - the privatization of public transit was a red flag in Councilmember Mosqueda’s office. I was tasked with looking into it, and getting a better idea of what this proposal would mean to workers, for road safety, and transit access. I started with the Mayor’s Office, aiming to get a better understanding of what their outreach had been, and who was requesting this privatization effort. While I never got an answer to the “who the hell wants this?” question, I was assured that “Labor [was] on board.” So, imagine my surprise when I checked with the union that represents bus drivers, only to find out they hadn’t even been informed of this proposed change. There were also unanswered questions in particular around road safety - subcontractors to public agencies in transit have, in my research, been less safe for other road users. A combination of relatively lax training and sub-par wages and benefits, and it’s no wonder. Given street safety issues in Seattle, this was also problematic.

Ultimately, our office came to the conclusion that this section of the bill was not in the best interest of the city as drafted, especially with the myriad of unanswered questions. At one point, the Mayor’s Office’s representative raised concerns about our opposition, suggesting that if we didn’t spend the money, then voters might not renew the funding source, one that is a combination of two of the most regressive taxes in Seattle. Apparently I’m insane, because that’s the only way I can describe the look I was given when I suggested to the Mayor’s Office’s representative that maybe - just maybe - this means we should trim the TBD by $20, and show some good governance pending a clear plan to either increase capacity for Metro, or more swiftly (and effectively) upgrade right-of-way for more bus-only lanes and transit infrastructure? It was made clear to me that their office was not, in fact, interested in reducing a tax that disproportionately impacts poorer households, often poorer households that don’t have access to reliable transit. Silly me.

And the point?

That’s a long story to get to my point: folks, we’re in an interesting spot with respect to taxes in Seattle. Whether it’s the TBD (which is now being spent on private transit - since the City Council opted against allowing it, King County subcontracted for their Via service, and now it’s being subsidized by the City through the TBD, a creative way, I guess, to get around the clear direction of the Council on this issue), the fight over the Sweetened Beverage Tax, or the Mayor’s new proposal to tax oil heating systems, our system has a disproportionate impact on low-income households - and it’s getting worse.

Who Pays What?

Before going too much into this - one question that we rarely hear or see posed to politicians: what do you believe is an appropriate share that businesses should pay in taxes to fund government? Is it 50/50? Is it 60/40 residents, or maybe 60/40 businesses? Because where you stand on this question really influences (or should) where you stand on how we implement revenue options in Seattle.

This was an exercise in which I engaged during the EHT discussion. The question I posed to Central Staff: how much of various taxes are paid by businesses, and how much by residents (for general fund purposes)? Because of limitations in access to data, I was essentially limited to property taxes, sales taxes, and B&O taxes. The result: residents pick up about 66% of property tax revenue in Seattle and 53% of sales taxes. Businesses are 100% of B&O taxes. When looking at just these three, businesses came out paying slightly more than 50% of tax revenue collections in Seattle.

What this didn’t include: car tab fees and taxes (that would have required information from the State, which would have taken more time to get than we had), or sugary beverage tax collections (which was unclear at the time - we now know that the overwhelming majority of these taxes are passed on to consumers). With the EHT proposal at $75 million-per-year, the balance would have tipped slightly - 2-3% of an uptick in business share of tax revenue for the city. Some back of the napkin math suggests that the sugary beverage tax revenue has tipped the scale 1-2% toward non-business residents.

Of course, we were also looking at pending impacts of the federal tax cuts that greatly benefited some of the largest corporations. So I dove into the federal tax numbers, and there we see that 47% of federal revenue (before the tax cuts in 2016) came from personal income taxes, 9% from corporate income taxes, and 34% from payroll taxes (typically split 50/50 employer/employee - think Medicare and Social Security), with the remainder coming from excise, estate, and other taxes and fees.

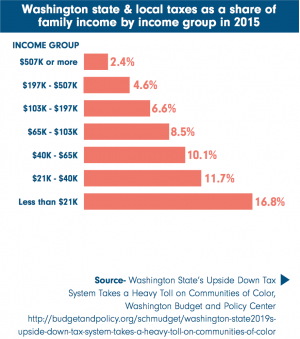

Add to all of this the inverse nature of our tax collection system on a socio-economic scale. Where the wealthiest households are paying as little as 3.3% of their income in state and local taxes, the poorest are paying closer to 18% of their income. Our system is a mess.

Sweetened Beverages, Oil Furnaces, and the Sales Tax “Rebate” Program

Broadly, Washington State has exhibited a desire for a nexus between a tax and what it is funding. I’ve talked with folks in other parts of the country who don’t fully grasp this near-obsession we have with the nexus of one thing to another in revenue strategies. That’s not to say it’s universally applied, but when the City of Seattle attempted to levy a tax on specialty coffee drinks (the “latte tax”) in order to fund childcare and pre-K, it was swiftly rejected by voters. Part of the argument against the Employee Hours Tax was that more jobs doesn’t mean more homelessness (ignoring the fallacy of such a simplistic approach to that revenue diversification strategy).

So, when the Seattle City Council adopted the Sugary Beverage Tax (SBT), it made a choice: revenue generated from this admittedly regressive tax should be reinvested in food access and health programs that target communities most impacted by sugary beverages - often low-income, often communities of color. The SBT was supposed to serve two purposes (as SCC Insight journalist Kevin Schofield points out): decrease consumption of sugary beverages (much like tobacco taxes are designed to decrease tobacco use) and use funds to promote healthy food access and education.

What we have learned: the SBT has not succeeded (thus far) in reducing consumption of sugary beverages. As a result, there has been even more revenue generated than anticipated. And here has begun our city’s journey toward what to do with that extra revenue.

As has been reported ad nauseum, the Mayor’s office wanted to use extra funds generated to fund general fund programs. A majority of the City Council, meanwhile, wanted to ensure that those extra funds are reinvested in the communities most impacted by the tax: low-income communities and communities of color. If consumption isn’t decreasing, after all, doesn’t it make sense to ramp-up investment and collaboration with community-based organizations to improve public health?

But also: that there is a push at all to tax poor households even more, worsening the inequitable tax system in Seattle, in order to fund general fund priorities while being hostile toward business taxes that target the wealthiest businesses and people in Seattle is antithetical to the purported values of our city. Some have made the argument that because the endorsed budget for 2020 assumes some of those dollars be spent in the general fund, we should just wait to implement a clear policy of how those funds are invested.

The problem with that argument: that is what Seattle has been doing to poor neighborhoods and communities of color for generations. That is disinvestment in action - telling poor folks to wait for the investment they have not seen for decades in order to appease some of the largest corporations in the world. That is the perpetuation of institutional classism and institutional racism. To that end, good on the supermajority of the City Council for refusing to make communities keep waiting for some semblance of equitable investment.

The New Push for Oil Heating Tax

Recently, the Mayor has proposed a tax on oil furnished to oil furnaces in Seattle. Being billed as a way to “combat climate change,” this proposal would target the remaining houses in Seattle that use oil furnaces for heating, ostensibly with the goal of getting them to convert to electricity. As has been reported, the majority of houses that use oil heating are in lower-income census tracts, and as I understand, many are rental units.

What this means in practice: lower-income folks, in particular renters, will see their heating costs increase as a result of this tax. For renters in particular, this also means there will be no recourse to actually convert to electric heat. Much like the Sugary Beverage Tax, this will have an inequitable impact on lower-income households. I know what you’re thinking: but we can just implement a program to help fund conversions from oil to electricity! Unfortunately, we can’t - the Washington State Constitution - Section 10 - prevents jurisdictions from this type of activity.

There’s another factor that I hope policy-makers will consider: oil furnaces definitely contribute greenhouse gas emissions. But in Seattle, they make up a whopping 2% of our overall emissions as of 2016. Compare that to Natural Gas (24.8%), or cars and light trucks (51%), and it seems this is not an area in which we will see significant reductions in carbon emissions by attacking in this manner.

Don’t get me wrong: a pathway to eliminating oil furnaces makes most sense. Through land use regulations that disallow permitting for any new oil furnaces, for instance (which may be the case already - I’m just too lazy to look it up). But if we’re going to tax a product that provides heat to households that are more likely to be lower-income, while not doing the same for natural gas, or while our city is kowtowing to anti-bike activists in favor of cars moving faster…it really does not seem to be in line with our city’s purported equity values.

The Sales Tax “Rebate” Program

Conversely, the Legislature did a phenomenal job this last session with HB 1406, co-sponsored by Rep. Nicole Macri (D-43) and Rep. June Robinson (D-38). It is common knowledge that sales taxes in Washington are a huge contributor to the tax inequities. With this bill, the State is now providing an avenue by which these taxes can be reinvested locally for affordable housing and homelessness response efforts, complete with bonding authority to frontload these investments.

The City of Seattle recently took advantage of this scheme, generating $50 million for housing programs to help get folks off of the streets. While this is a woefully inadequate amount (about 5% of the overall need in King County), every piece matters. Assuming the County takes its portion, and the alliances of Eastside cities, and a new alliance of South County cities, combined to do the same, this can be a significant boost in funding for permanent housing across King County (some estimates say upwards of $150-200 million).

Suffice it to say…

Our tax structure is broken. In addition, for generations our state and local governments have exacerbated income and racial inequality through community divestment and uneven commitment to stated values. Our entire state (including all of the municipal and county jurisdictions) is long overdue for major tax reform - implementing a progressive income tax, reducing sales and property taxes, capital gains taxes (including for high-value property transfers), a complete re-write of the B&O tax (and implementation of a progressive payroll tax), and more that can and should be considered.

In the interim, it is incumbent upon our elected leaders to do everything possible to make equitable investments with our inequitably collected tax dollars, not further exacerbate the system. Big ups to the Seattle City Council - in particular Councilmembers Herbold, González, and Mosqueda - for being some of the leaders we need to push back against politicians who want to reverse-Robin Hood our city. As we consider who will represent us this November, it is crucial we all hear more and better understand where every candidate stands on tax policy and their position on equitable investment throughout our city.